Manténgase sano!

- Sydney Murphy and Consumer News

- Posted August 29, 2022

Alzheimer's: Who Is Caring for the Caregivers?

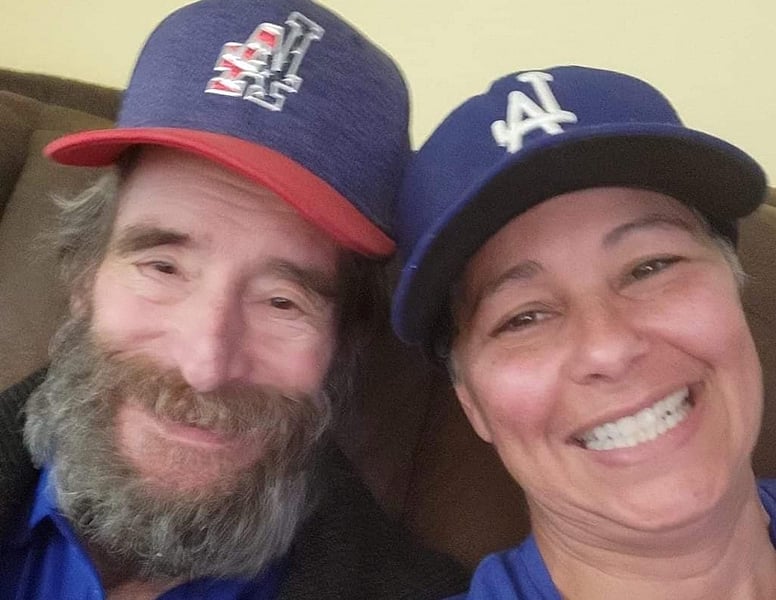

Katherine Sanden drove over 1,400 miles, from California to Nebraska, to care for her beloved uncle after he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's in November 2020, but seeing him after years apart was more devastating than she could have ever imagined.

Like Sanden, many family caregivers are thrown into the deep end with little to no experience helping someone with Alzheimer's. Though some find outside support to help them navigate health care systems, Sanden struggled to get that for her uncle in Nebraska.

After living with him in a small town for three months, Sanden found herself needing to learn ways to advocate for her uncle Larry. The 50-year-old was faced with a completely different health care system than the one she knew in California.

Sanden described the two states as drastically different worlds. "It's like living on two separate planets as far as services and what care is available," she noted.

One of the major challenges: Sanden had to jump through hoops to transfer his care to California after moving her uncle to her home earlier this year. Her social worker, whom she found through a local resource center, offered Sanden much needed guidance on navigating the health care system. Sanden also took a class and met with a lawyer to get help completing the paperwork necessary to transfer his care from Nebraska to California, and then she filed for conservatorship after her uncle's son gave up guardianship in Nebraska.

"I didn't have a social worker or an advocate in Nebraska, I had to do everything,"said Sanden.

The move across state lines has been financially challenging: Besides relying on her savings to support herself, her uncle needed a new bank account set up by his caregiver when they moved. But in California, banks only recognize conservatorships.

"I contacted my social worker, I don't even know what to do. I don't even know where to start. I don't know who to talk to. So, I was very grateful for her because she's like, this is ridiculous. It's just been ... a little bit of a nightmare,"Sanden said.

The emergence of COVID-19 only made it harder to care for loved ones with Alzheimer's.

"During the pandemic, we saw a huge increase in our care consultation need because support groups were meeting virtually and education programs were delivered virtually, so that meant many constituents couldn't participate,"said Elizabeth Smith-Boivin, executive director of the Alzheimer's Association's Northeastern NY Chapter.

Smith-Boivin described how devastating some calls to the association's helpline were at the beginning of the pandemic. In one call, a man who was caring for his wife said he's tested positive for COVID-19. At the time, he was trying to isolate from his wife, who couldn't understand why he needed to distance himself from her. She kept knocking on his door and crying, begging for him to come out, but he couldn't.

Added burden of COVID-19

"The calls like this at the beginning of the pandemic were heart-wrenching,"said Smith-Boivin.

Sanden also shared the struggles she faced while caring for her uncle during the pandemic.

"People don't understand how difficult it is to meet someone's needs who can't articulate his own, doesn't know what his needs are and has absolutely no control over how he feels,"she said.

According to Smith-Boivin, what the Alzheimer's Association has learned is that they never fully understood the impact of social isolation. Health care providers and support organizations had no idea how devastating not only the emotional and mental impact of this would be, but the physical impact as well: The United States saw an 8.7% increase in the national death rate for Alzheimer's in the first year of pandemic alone.

Though some deaths could have been due to undiagnosed COVID-19 cases, the Alzheimer's Association recently launched a study looking at how the new coronavirus may affect the brain, and dementia risk, in the long run.

Though there are support groups offered across the United States, the major challenge introduced in 2020 was the necessity to make them virtual due to social distancing and travel bans. That left those who were not technologically savvy out in the cold.

And although home health aides can provide support for caregivers, the pandemic has led to a shortage of these critical health professionals.

Take Nebraska, for example: The number of home health and personal aides in Nebraska dwindled from 11,890 to 7,720 in 2020. That forced thousands to become caregivers for their loved ones. In 2020, more than 11 million Americans provided an estimated 15.3 billion hours of unpaid care with little or no mental health support.

"What we often had to do was teach family members techniques of caregiving,"said Smith-Boivin.

With no prior experience caring for a sick loved one, Sanden relied on books to teach herself how to care for her uncle on her own. She read "The 36-Hour Day,"a guide to caring for people who have Alzheimer's disease and other dementias.

"I've had to adapt and overcome. Every day is the same, but every day is a different day,"said Sanden.

Teaching themselves how to cope

After learning that scheduling activities and forming routines throughout the day can be helpful, following a morning schedule became a daily routine for Sanden and her uncle. Sanden quit her job as an accomplished chef to take time to spend with her uncle. She relied on her savings to support herself because she couldn't work while caring for Larry. She said that she tried to keep a strong composure, though it was hard to stay calm a lot of the time.

"Any opportunity I get to act like a nut and jump around and make him laugh and mimic me -- that's been our saving grace,"Sanden said.

While caring for her uncle was an opportunity for Sanden to get to know him on a deeper level, it took a toll on her own mental health. She described her anxiety about the signs of her uncle's rapidly declining health.

"I know he's not getting better. I know he will never get better. With him not eating, it has stressed me out beyond belief because I'm not ready,"Sanden said.

Sanden was in therapy for six years and learned ways of coping with the stress that she feels as a caregiver. She routinely practiced yoga and took her two dogs, a Husky and a Border Collie, to the park with her uncle to get fresh air.

Sanden spoke about the hardships she faced and the emotional impact caring for Larry had on her.

"It's watching somebody deteriorate with no choice in it. It's really frustrating in retrospect," she said. "He has a condition that will never improve."

Sanden recognizes she is fortunate to have family members who support her in any way they can. "I'm lucky that I have my mother and I have my partner who support me. There are a lot of people out there who don't have people supporting them. I have resources here in California, but while living in Nebraska, I had none,"she said.

The problem is pressing: As the number of older Americans grows, so will the number of Alzheimer's cases, according to the Alzheimer's Association. By 2050, the number of people over 65 with Alzheimer's may grow to a projected 12.7 million, escalating the importance of improving support for family members and loved ones stepping in as caregivers.

Watching her loved one near the end of his life was heartbreaking for Sanden. "I didn't want to watch him suffer. I wanted to make sure he passed comfortably,"she said. He did, dying peacefully earlier this summer while surrounded and supported by family and friends.

Sanden returned to school this month to earn a restaurant management certificate. Though she still practices her culinary skills, Sanden has decided to become a "life transition doula,"a person who supports others in situations similar to those she faced.

"Larry inspired me to go to culinary school, and he has now inspired me to pursue my calling -- the career I was born to have,"Sanden said.

More information

Visit the U.S. National Institute on Aging for more on Alzheimer's.

SOURCES: Katherine Sanden, Alzheimer's caregiver, California; Elizabeth Smith-Boivin, executive director, Alzheimer's Association's Northeastern NY Chapter